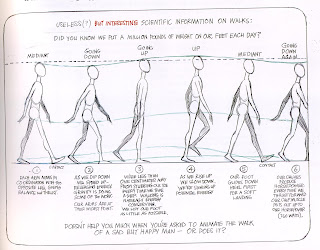

01 Animating a walk is one of the

hardest things to get right.

It’s a process of falling over but catching

yourself just in time. If we don’t put our foot forward then we could fall flat

on our face, we are going through a series of controlled falls.

We lean forward with our upper bodies and

throw out a leg just in time to catch ourselves. The slower we walk, the easier

it is to keep our balance.

Each arm moves in co-ordination with the

opposite leg, this helps us to balance.

As we dip down gravity is doing some of the

work, our arms are at their widest point.

02 We’re less than a centimetre

from stubbing our toe each time we take a step, we lift our foot as little as

possible.

As we rise up, we slow down

Foot glides down heel first for a soft

landing.

All walks are different; no two people in

the world walk the same. When actors are trying to get into character they try

to work out how he/ she walk. You can usually recognise someone’s walk even if

you can’t see them clearly.

03 There is a lot of information

about somebody in their walk and we can read it instantly. One thing to look

for is how much up and down movement there is.

04 Women often take short steps

and walk in a straight line, the legs are closer together and there is very

little up and down movement.

05 Men usually walk with their

legs further apart with lots of up and down head and body movement.

If we trace or rotoscope a walk from some

live action footage it doesn’t work very well and appears to float. In

animation we should caricature real life and increase or exaggerate the ups and

downs. We just don’t get a feeling of weight from smooth, level movement.

06 Its the up and down positions

that give a feeling of weight.

It’s important to understand how a normal

walk works before we can start to build or invent walks of our own.

06A First we’ll make two contact

positions. In a normal, conventional walk the arms oppose the legs to give

balance.

08 Because the leg is straight up

on the passing position it lifts the pelvis, body and head slightly higher.

10 Next we put in the up position

or the push off. The foot pushing off lifts the pelvis body and head to its

highest position. Then the leg is thrown out to catch us on the contact

position, so we don’t fall flat on our face.

12 So in a normal walk the weight

goes down just after the contact position and the weight goes up just after the

passing position.

12A The first thing to do in a

walk is to set a beat. Generally people will walk with two steps per second.

That means from contact to contact there will be 12 frames.

This a little bit difficult to divide up

though and some of the inbetweens will need to be on ‘thirds’.

It’s a lot easier to animate a walk on 16’s

or 8’s (3 steps per second), it’s easier to decide where to put the inbetweens.

At first it’s better to animate a walk

across the page as opposed to trying to animate a cycle.

Just to make sure you understand that

timing is the most important part of the process let’s have a look at some

different ones. Remember we are working with 25 frames per second.

WRITE ON BOARD 4 frames = A very fast run

(6 steps per second)

6 Frames = a run or very fast walk (4 steps

per second)

8 frames = slow run or cartoon walk (3

steps per second)

12 frames = brisk, Natural walk (2 steps

per second)

24 frames = slow step, for an old person’s

walk. (1 step per second)

The Passing Position or Breakdown

13 One way to build a walk is to

start with three drawings, first make the two contact positions

Then put in the middle position, passing

position or breakdown. Raise it up higher than normal,

Try it again but put the passing position

down below the contact positions, this will give us a very cartoony walk but

will still give us a feeling of weight.

14A Try it with a squash or bent

like a kidney shape.

Or bent backwards

We can delay the foot or do this in a slow

step, it will look like a sneak.

The animation medium is very unusual in

that we can accomplish actions that no human could and make it look convincing.

15 Deciding where to put the

passing position is a key to animating a good walk, then we can decide what to

do with the head, arms feet, the possibilities are endless. The main thing is

to understand the mood of the character in question.

16 Once we’ve settled on a style

of walk for the character we can start to think about counteraction and overlapping action. With a character who has a

belly the stomach mass can go up as the body goes down.

It’s the same with drapery, when the

character goes up the drapery goes down, this applies to things like hair,

breasts and any other appendages.

16A One tricky thing to animate

is a woman walking from a back view. The bum moves in the direction of the

forward foot. Drapery would oppose the hips with a delay and then settle.

17 In the 50’s and 60’s studios

like UPA put all these principles in place then played around with them.

17A Eventually, we find we’ve

come full circle in the realisation that no two characters walk the same.

19 Loosening it up:

Starting with a simple walk, arms opposite

legs, shoulder forward when arms go forward and back when shoulder goes back.

20 Front view, Tilt the

shoulders, it’s taking the basic plan and building on it.

On the passing position the hips and

shoulders are more or less straight.

21 To give more character to a

walk, tilt the head once the hips and shoulders are down.